HIV-Positive Mother Struggles through the Covid-19 Pandemic

PHOTOS AND TEXT BY

Ria Torrente

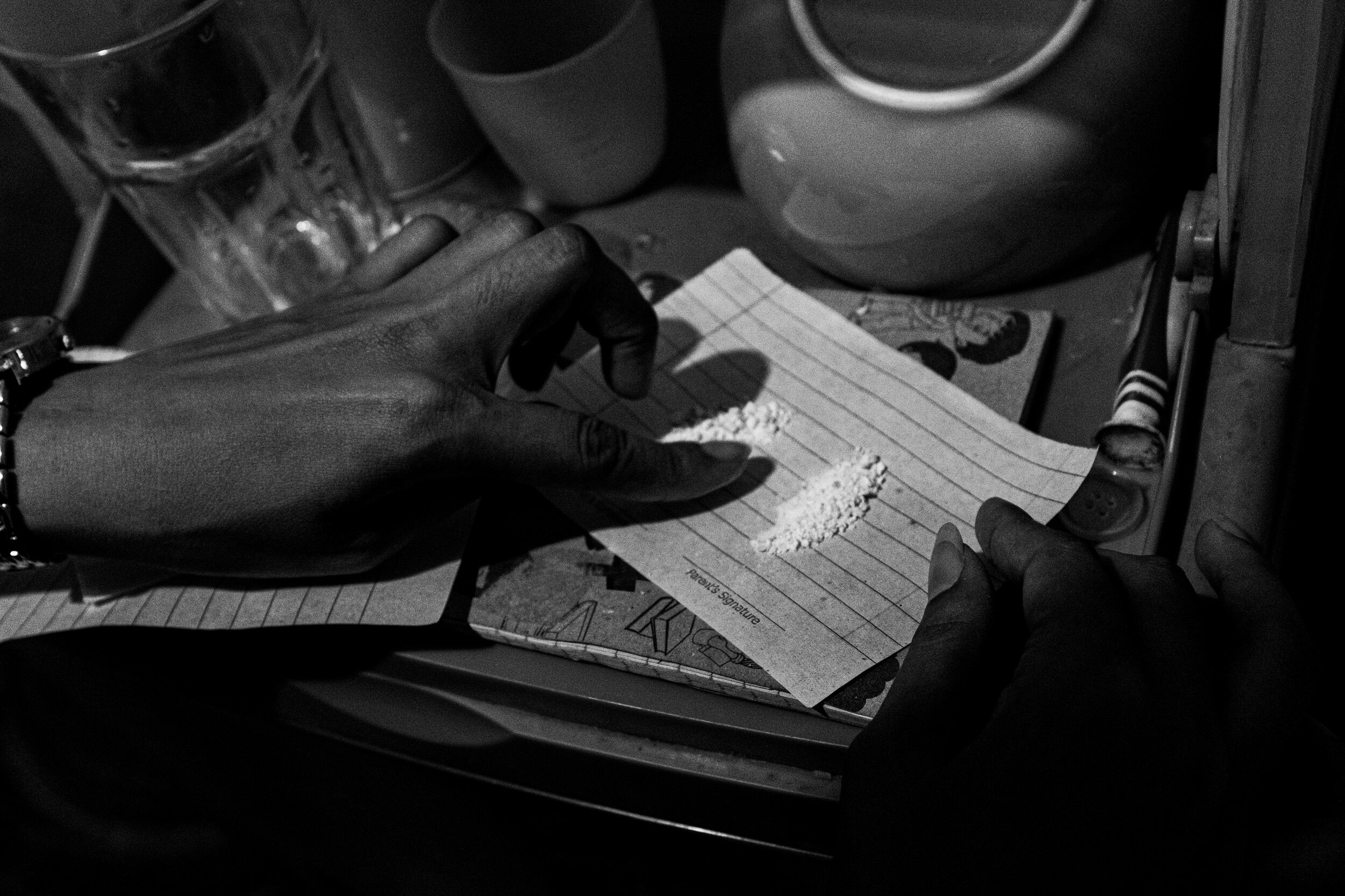

In addition to stigma and discrimination, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought new obstacles in the fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic. People living with HIV are vulnerable to Covid-19, and government healthcare coverage may not offer enough protection.

Mace*,32, makes it a point to replenish their bottles of antiretroviral (ARV) medicine when only 10 tablets are left in their monthly supply. But when the government imposed a lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic last year, she found herself unable to travel to her treatment hub in Pasig City for a refill.

She and her youngest daughter, Tiffany*, 4, were both diagnosed with the infection in 2017. Her husband separated from her upon learning of her HIV diagnosis. Since the pandemic, Mace has been shelling out an extra P150 to P180 to have their medicines delivered via a courier service.

ARV drugs, which Mace and Tiffany get for free at the treatment hub they are enrolled in, help them lead long and healthy lives while there is still no effective cure for HIV/AIDS.

In addition to stigma, discrimination, and lack of public awareness, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought new obstacles in the fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Limitations in HIV testing, treatment, and ARV drug supply, as well as financial worries, are affecting the lives of people living with HIV (PLHIV), especially those who are economically disadvantaged.

Mace relies on the income of the sari-sari or variety store that she opened at her home in January last year with the help of the NGO Project Red Ribbon. She lives in a small shack that is now divided into two cramped spaces for the store and her bedroom. She pays P500 for her monthly rent.

“There’s not much income since my store is within an alley. It’s not visible from outside,” she explained in Filipino.

Her two children stay with her ex-husband in Pasig City most of the time. On some days, she can bring them home with her in Cainta, Rizal.

Every three months or when funds are available, she lines up at the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) in Manila to get cash assistance for indigents and vulnerable individuals. She receives P10,000 for herself and Tiffany.

But these days, she has to wait longer for the DSWD announcement because of the pandemic.

‘Expand the coverage’

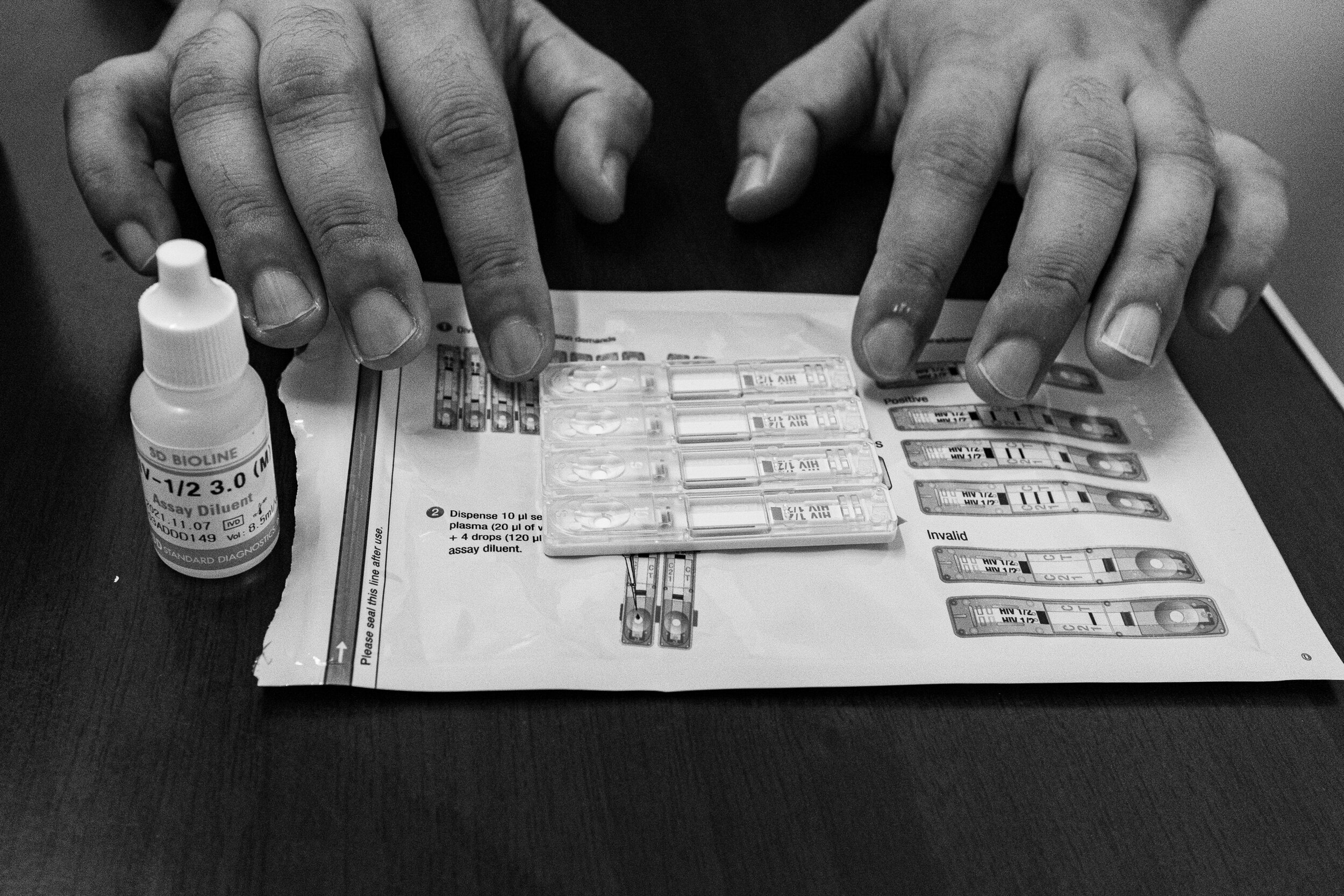

Ron, 43, an information technology professional and a person living with HIV (PLHIV) who volunteers as a counselor at LoveYourself Inc., a HIV testing, treatment and counseling clinic, said a number of patients who had lost their jobs amid the pandemic were struggling to keep up with their contributions to the state-run Philippine Health Insurance Corp. (Philhealth).

“This affected their access to the OHAT package,” he said.

PhilHealth introduced the Outpatient HIV/AIDS Treatment (OHAT) package in 2010 to provide the PLHIV community a baseline level of help for treatment.

While antiretroviral therapy (ART) is free, the OHAT package doesn’t cover treatment of other illnesses related to HIV/AIDS.

“We need to expand the PhilHealth coverage. It doesn’t include other laboratory tests, vaccines and other treatments for opportunistic infections and comorbidities. We also need to take care of the mental well-being of our clients,” Ron said.

Ron said that for HIV patients, flu and pneumonia vaccines are required prior to vaccination for Covid-19. “The costs of these vaccines alone add burden to most of our clients who are not able to afford them.”

The rate of HIV infection has been increasing in the Philippines even before the Covid-19 pandemic. From January to March 2021, a total of 2,786 newly diagnosed cases were reported, wherein 2,647 were male and 139 female. Twenty-five females, with ages ranging from 15 to 36 years old, were pregnant.

A total of 10 children below the age of 15 were also diagnosed with HIV. Two were infected through sexual contact and six acquired the infection through mother-to-child transmission. Two children had no data on the mode of transmission.

Suob and mefenamic acid

Mace hasn’t updated her PhilHealth contribution. She stopped working when her health worsened before her HIV diagnosis. She’s afraid of going back to a regular job because of her condition.

“There were instances when I fainted. I always feel dizzy and weak. My body is not as strong as before,” she said.

The risk of getting infected with Covid-19 has also affected her mental health. “I worry a lot because I’m thinking about what will happen to us in this pandemic. It’s easy for Tiffany and I to get infected with any disease.”

Whenever she’s not feeling well, she does suob (steam inhalation) or takes over-the-counter medicine like mefenamic acid. Tiffany’s healthcare costs will be covered by her ex-husband if she gets sick.

Mace is thankful to the organization and advocates who help people like her and Tiffany.

“It was already harder for me financially before the pandemic. We are able to get by these days through their assistance,” she said.

Mace wants her daughter to finish school and live free of discrimination. ‘I pray that my daughter will become closer to God,’ she said.

She also hopes that a cure for HIV will finally be discovered.

*Mace’s and Tiffany’s names were changed for their protection.

This story is one of twelve photo essays produced during the Capturing Human Rights fellowship, a seminar and mentoring program jointly undertaken by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism and the Photojournalists' Center of the Philippines.